I feel the same way about housing benefit that Millwall fans feel about their football club, no one likes it and I don’t care.

On the left wing of politics housing benefit is called “‘taxpayers’ subsidies to landlords” while the right talk about how spending on housing benefit is ‘out of control‘.

Despite arguments by some, the fact is that housing benefit is here to stay. Because;

- It stops people who lose their jobs from being evicted

- It pays for the rent of people who rely on state pension or disability benefits for income

- It funds a big chunk of the cost of building new social housing (because housing associations or councils borrow for part of the cost of this housing against future rents, which partly come from housing benefit)

Perhaps most importantly, the reason house benefit is hear to stay is because it accounts for a significant proportion of the income of poorer households.

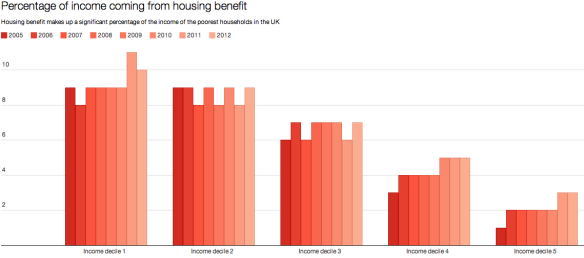

This chart shows the percentage of poorer people’s income that comes from housing benefit;

You might say that housing benefit isn’t really income because it goes to the landlord. This doesn’t really make any sense. It’s like saying my wage isn’t really income because it pays for my mortgage. People are getting something for this money.

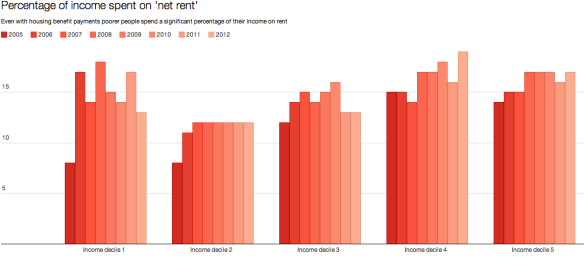

None of this is to say that the current housing benefit system is perfect. Far from it. Just look at this chart which shows how much, on average, poorer people pay on rent even after housing benefit is taken into account;

‘Net rent’ (ie rent costs on top of the amount paid for by housing benefit) still accounts for over 10% of the incomes of poorer people.

There are a number of problems with the current housing benefit system, including;

1. Low take up

In 2009 to 2010, the number of people that were entitled to but not claiming Housing Benefit was between 0.75 million and 1.14 million. The total amount of Housing Benefit unclaimed was between £1.85 billion and £3.10 billion.

2. Stigma

In a recent survey, 4 out of 5 landlords said they would not accept tenants who receive housing benefit. This gives even more power to landlords who do have tenants on housing benefit, because they know their tenants are not going to be able to easily shop around.

3. Paid in arrears

Like most benefits, housing benefit is paid in arrears. This can cause problems for tenants, especially if there are any delays or complications, if they can’t afford a deposit or if any other of the number of things that can go wrong with administration of a complex benefit go wrong.

These problems with housing benefit are not being addressed in contemporary political debate because housing benefit is so unloved. Perhaps it’s time to change that, for example by proposing a ‘basic income‘ for all citizens.